Three-Character Classic.

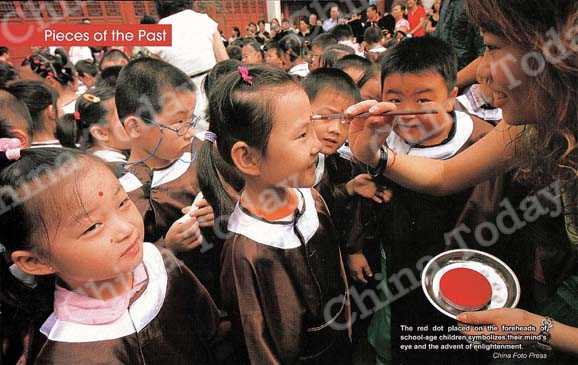

THE Chinese people have always set great store by rudimentary education. Centuries ago, boys of the age of five or six began their schooling with classes in ethics intended to guide them along the path to morally upstanding citizenship.

Precocious Wisdom

All Chinese people know the story of Kong Rong, descendant of Confucius (surnamed Kong) who lived in the late Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220). Kong Rong was the sixth of seven brothers. One day during his childhood, Kong Rong's mother placed seven pears on the table for her children. Kong Rong picked the smallest. When his pleased but bemused father asked him the reason why, the four-year-old answered, "I'm young, and should leave the bigger pears for my elder brothers. But as I'm also an elder brother, I should leave a bigger pear for my younger brother." This story is recorded in San Zi Jing (Three-Character Classic), an ancient textbook of rudimentary education.

Morals and ethics were a predominant aspect of Chinese education within the ancient Confucian culture. This emphasis gave rise to the well-known maxim: "A child's potential as an adult is apparent when he is three; how he will actually turn out is apparent by the age of seven." This saying alerted parents to the need to observe the personality traits of their children from infancy, rewarding good behavior while simultaneously discouraging antisocial tendencies. Behavioral defects that persisted by the time a child reached the age of seven were believed to be irrevocable. Modern psychology endorses the scientific soundness of this theory. As a person's success in life depends largely on his or her conduct within a social environment, rudimentary education shapes the course of his or her entire life.

The Rudimentary Education "Bible"

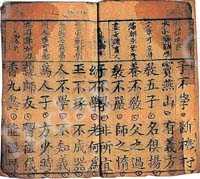

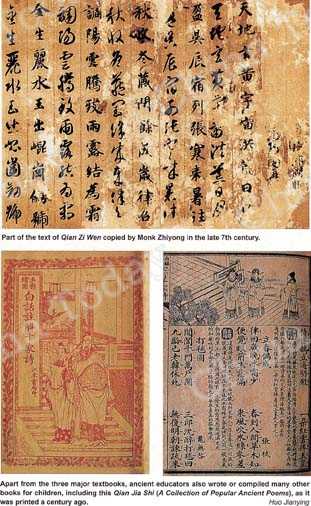

It is incredible to consider that, until the advent of modern education and public schools in the latter half of the 19th century, Chinese rudimentary teaching materials remained unchanged for thousands of years. Outstanding among early primers are San Zi Jing (Three-Character Classic), Qian Zi Wen (Thousand-Character Essay) and Bai Jia Xing (Book of Family Names). Other commonly used textbooks were Qian Jia Shi (Collection of Popular Ancient Poems), Dizi Gui (Code of Conduct for Students), and Ming Xian Ji (Book on Celebrities and Men of Virtue).

San Zi Jing was the most commonly used, and consequently influential, of all primary school textbooks. It was introduced to Japan and Korea centuries ago, translated into Russian in 1727 and later became available in English and French. UNESCO listed the book in its series on moral education for children in the autumn of 1990. It has since been promoted and published throughout the world.

A private school in the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Morals and ethics were a predominant aspect of Chinese education within the ancient Confucian culture.

San Zi Jing was written by Wang Yinglin, the great 13th-century Confucian scholar and educator, for children in his clan. It is composed of three-character rhyming stanzas, four stanzas forming one sentence. San Zi Jing's 1,415 characters capture succinctly the essence of the Chinese value system and code of ethics. This masterpiece has always been generally regarded as a humanities encyclopedia for children, a systematic pedagogical aide for teachers and an indispensable reader for parents.

The text begins with the importance of education, citing Mencius as an example. Mencius (surnamed Meng) lost his father when he was two. His widowed mother tried to make ends meet by weaving and selling cloth. No matter how hard life became, she always took the time to create the best circumstances for her son's education. Mencius was a clever but mischievous boy. In his early years, he and his mother lived near a tomb area. Mencius quickly became familiar with the rituals involved in funereal ceremony. His mother, believing this to be an unhealthily morbid environment, moved to town near a market fair. Before long, Mencius began behaving in the manner of a shrewd trader. Seeking to curtail this tendency, his mother moved again, this time to a dwelling near a school. As she expected, young Mencius proved a bright student and a promising scholar. As he generally finished his schoolwork way in advance of the other children, however, he would steal out of the classroom to play. On one occasion he stayed away too long, and his teacher went to his home looking for him. Mencius's mother reacted to the news of his truancy by cutting all the threads on her handloom, and telling her son to reconnect them. Mencius was at a loss as to how to restring this entangled mass of broken threads. This was his mother's way of showing him that study is comparable to weaving, as the complex lines of knowledge are similar to the threads on a loom that, once broken, can never be reconnected. From that time onwards, Mencius studied very hard. He grew up to become a respected and celebrated Confucian sage.

This story is summarized in just 12 characters in San Zi Jing that translate to the effect: "Back in the time of Mencius' mother, she was choosy about whom to neighbor. When the son would not learn, she cut her loom thread to warn." In another 12-character line, San Zi Jing also holds: "Feeding (a child) without teaching him is the father's fault. To teach without severity is the teacher's laziness." So in the conventional concept, both parents and teachers are considered crucial to children's education.

The textbook is in two sections; the first examines the basics of humanities, nature, Chinese history ancient classics; the second expounds on moral education and codes of ethics, citing many outstanding personages, such as Mencius and Confucius as role models.

Thousand-Character Essay

Qian Zi Wen (Thousand-Character Essay) is a textbook equal in importance within rudimentary education to San Zi Jing. Its author is Zhou Xingsi who lived in the early 6th century. The two celebrated calligraphers Zhong Yao and Wang Xizhi are also said each to have compiled a Qian Zi Wen prior to that by Zhou Xingsi. Both were aesthetically pleasing, but lacked the deep profundity of Zhou's edition. They have consequently disappeared from view.

Apart from the three major textbooks, ancient educators also wrote or compiled many other books for children, including this Qian Jia Shi (A Collection of Popular Ancient Poems), as it was printed a century ago. Huo Jianying

Zhou Xingsi was renowned for his breadth of knowledge, quick wits and literary eloquence. His reputation earned him the appointment as personal secretary to Emperor Wudi of the Liang Dynasty (502-557), during the Southern Dynasties Period (420-589). The emperor commissioned the compilation of a Qian Zi Wen textbook for the benefit of his sons and nephews. He ordered the selection of 1,000 characters from the calligraphic works of Wang Xizhi, and instructed Zhou Xingsi to compose them into a rhyming essay. Zhou spent an entire night compiling these unrelated characters into a literary masterpiece. Upon reading the essay, the emperor was delighted and bestowed a generous largess on Zhou for his labors. The supreme effort of creating this literary masterpiece is said to have turned Zhou's hair white overnight.

The Qian Zi Wen textbook was intended for the exclusive use of the imperial family. It was thanks to Monk Zhiyong of the late 7th century that it became available to the common people. Zhiyong was the seventh-generation descendant of Wang Xizhi, and also an accomplished calligrapher. He spent three decades transcribing more than 800 copies of his own edition of Qian Zi Wen, in both regular and cursive script, and donated them to various temples around Zhejiang Province. Before long recitations of the textbook could be heard throughout the nation.

Qian Zi Wen begins with antithetical descriptions of the universe that traverse the vastness of the heavens and the earth, encompassing the rising of the sun and the eclipse of the moon, the change of seasons from summer to winter, precipitant rain and the formation of frost. The author's vision embraces the heavens and climatic phenomena that affect farming activities, nature and humankind, the lives of the people and the art of their governance, ancient scientific inventions and the arts of music and dance. The vast scope of topics that Zhou Yingsi covers within the designated 1,000 characters include astronomy, geography, history, politics, military affairs, culture, literature, arts, social life, ethics, and ancient saints and sages.

Mencius (left) is worshiped at the Confucius Temple in Qufu. Huo Jianying

Qian Zi Wen is composed of 250 four-character rhyming stanzas, within which are many allusions to ancient classics. It is generally judged as an even greater poetic epic than San Zi Jing, being imbued with still deeper beauty and poetic fascination.

Bai Jia Xing (Book of Family Names) constitutes the final component of this ancient textbook trilogy. Its purpose is to help children learn Chinese characters by memorizing the most common "old hundred" Chinese surnames. It examines the origins of surnames and details famous personages within various clans, their virtues and merits. Raising these role models gives grounding in ethics. Studying these three books was generally expected to take a year and a half, during the course of which pupils mastered more than 1,000 characters. This is more than what a second grader at a contemporary school is expected to cover.

These three pillars of pedagogical wisdom may have been superseded by more contemporary educative theories, but their influence lives on by virtue of being permanently embedded in the Chinese consciousness.

Children in Shenzhen experiencing for themselves how and what their peers studied centuries ago, including this guzheng class. China Foto Press

Copy Reference

Copy Reference