HONGJIANG City is little known in modern times, but historically it was a key port and bustling trade center full of riches, spendthrift lifestyles and opium dens. Located in a mountainous zone in the southern province of Hunan, Hongjiang's role as an important trade hub stretches back to antiquity. More than 3,000 years ago it lay on the trade route between China's interior and the Indian and Arabic Oceans, and the Red and Mediterranean Seas. During the Han and Tang dynasties, it was an important link on the Southwestern Old Silk Road, and in the Ming and Qing dynasties it was one of the first areas in China to see the seeds of capitalist commerce germinate. Despite its remote location, in the early 20th century the inhabitants of this small city enjoyed a luxurious lifestyle equal to that found in major metropolises like Shanghai and Nanjing. In 1920 electricity came to the town, telephones were introduced in 1929 and silent movies arrived in 1931. "At that time, we had everything Shanghai inhabitants had," says an official of the Hongjiang District Tourism Bureau, proudly recalling his city's past glories.

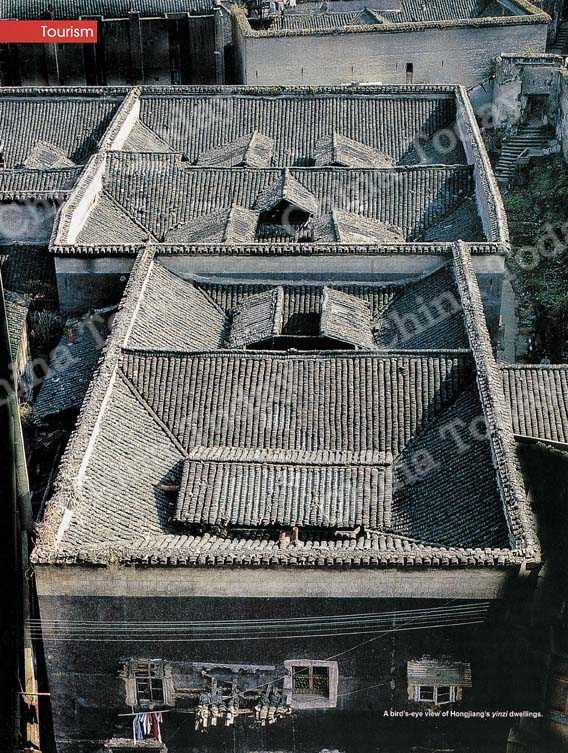

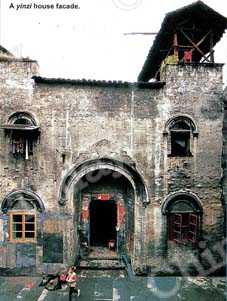

Hongjiang's yinzi houses, comparable in design to Beijing's siheyuan courtyards.

In the Ming and Qing dynasties Hongjiang was one of the first areas in China to see the seeds of capitalist commerce germinate.

A Crucial Trade Junction

Hongjiang owed its prosperity to its position on the Yuanshui River, an important tributary of the Yangtze linking various.big cities in south-central China, and Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan in southwestern China. Resources coming out of southwestern China, such as timber, herbal medicines and tung oil, had to change from the Yuanshui to Yangtze rivers here in order to reach Wuhan and Shanghai. Going the other way, commodities from Wuhan and Shanghai, such as cloth and foodstuffs, had to traverse the Yuanshui River to reach southwestern China, making Hongjiang a vital trade junction.

Before liberation in 1949, Hongjiang's wooden boats were the largest on the Yuanshui River. Each vessel was as high as a five-story building.

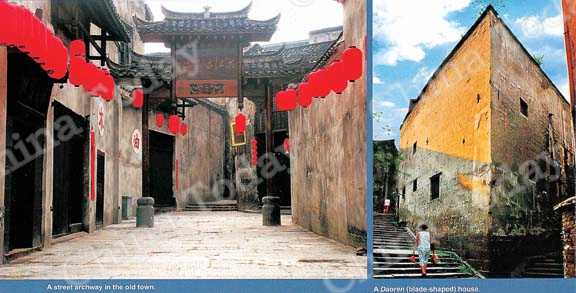

One of Hongjiang's many ancient streets.

Standing on Litouzui Dock, one of the places from which this city developed, 76-year-old Ruan Mingyi points to a fishing boat hauling in a net and reminisces, "Sixty years ago this river was covered with rafts and trading boats, and every day was a scene of flourishing business." According to historical records, at its peak this city of less than four square kilometers had 48 docks. A merchant in the Qing Dynasty described Hongjiang as a "large town of thousands of households." Of the city's population of 36,700 people, 15,000 were traders.

Various support industries thrived in this prosperous center of commerce. Wang Tiande is a veteran worker who was employed by a local shipyard at age 17. After retiring, he continued to ply his trade, repairing boats for fishermen. "At that time, Hongjiang was famous for its shipbuilding," he recalls. "Before liberation in 1949, Hongjiang's wooden boats were the largest on the Yuanshui River. Each vessel was as high as a five-story building. Several dozen of these boats could be found navigating the river at any given time, each one a self-contained floating village. It was a splendid scene."

Workers engaged in water transportation often worked onboard for one or two months at a time. Ships were fitted with all kinds of recreational facilities, such as musical instruments, food and beverages, and gambling equipment. The boats' roofs were covered in soil and used for growing vegetables, as well as raising chickens and ducks.

Prosperity Built on Timber, Opium and Tung Oil

The three key commodities traded in Hongjiang before liberation were timber, tung oil and opium. Yang Peicheng, now in his late 60s, is the son of a timber merchant. He experienced the prosperity of the timber business in the early to mid-20th century. The image that has remained strongest in his mind is the sight of the rafts employed annually by his father to transport timber to Nanjing or Shanghai. Each raft comprised three to five tiers of tree trunks fastened together to form a floating platform 30 meters long and 7 meters wide. Yang Peicheng recalls, "When a Hongjiang merchant floated a train of rafts downstream, he usually hired more than 10 sailors. The two most important roles were the rafting manager and accountant. The former was responsible for hiring sailors, negotiating prices and commanding navigation, and the latter for arranging the sailors' provisions and checking the quality, length and specification of the timber." Yang Peicheng claims that at peak times, the river was so packed you could walk across the rafts from one bank to the other.

Hongjiang residents enjoy a local Yang Opera performance.

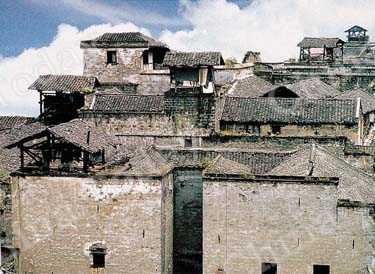

Conserved Ming and Qing dynasty architecture in Hongjiang old town.

The activities of the ambitious Hongjiang merchants were not limited to the timber trade however. Other raw materials were processed to accumulate wealth, most notably tung oil, an excellent anti-rotting and anti-moth varnish for wooden houses, boats and farm tools. Since the Ming and Qing dynasties, shipyards in coastal provinces such as Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian and Guangdong have needed a steady supply of the oil, and Hongjiang's large output and superior quality of its product ensured the commodity became central to the local economy. The oil was also exported abroad.

The third pillar of Hongjiang's economy prior to liberation was opium. Liu Huiwu, aged 79, is the son of Liu Yongtai, former owner of the Yongtai Trading Company. At one time Huiwu's father was the wealthiest person in Hongjiang. It is said dockers loaded opium onto the ships of the Liu family from six in the morning till dusk every day. The drug was traded for silver dollars, and according to local legend at nine o'clock each evening "The whole city could hear the sound of silver dollars being counted." A fire in 1934 initiated the Liu family's decline, but it was the 10,000 silver dollar ransom paid when Huiwu's father was kidnapped by bandits that sealed their fate. The ransom triggered panic withdrawals from the family's private bank, dealing a fatal blow to the family business.

The Liu family's decline is indicative of a general trend in the city's fortunes. On the one hand, Hongjiang traders were hardworking and capable, on the other they sought extravagant and indulgent lifestyles. Opium was not only traded, but also consumed by many in the town. Hongjiang's opium dens were once famous in western Hunan, and many of the town's rich were addicts. One story has a local spending 2,000 silver dollars on an opium pipe. The government's banning of the opium trade was no doubt a heavy blow to them.

In more contemporary times, the massive expansion of China's highway and railway system has meant Hongjiang has lost its geographical advantage, and commerce has gradually declined.

On the one hand, Hongjiang traders were hardworking and capable, on the other they sought extravagant and indulgent lifestyles.

Remains of the Ancient City

Hongjiang is a veritable museum of Ming and Qing dynasty architecture. As a commercial city, it features a distinct flexible and practical architectural style designed to accommodate both commercial and residential needs. Among the ancient buildings that have survived are 17 newspaper offices, 23 old-style banks, 34 schools, 48 drama stages, 50-odd brothels, 60 opium dens, 70 restaurants, 80 hostels, 100 workshops, 1,000 stores and 380 yinzi buildings.

Similar in style to siheyuan (compounds with houses around a square courtyard), yinzi buildings combine the features of southern Anhui residences and the stilt houses found along the Yuanshui River. They usually comprise two courtyards with two-story houses, although compounds featuring three courtyards with three-story buildings can also be found in the city. Third floors are generally linked by a bridge running north-south. The roofs of the houses slope towards the center, leaving a skylight to let in sunshine and fresh air.

Yinzi buildings are constructed of brick, stone and wood without a single iron nail, but they are nonetheless very solid structures. Practicality is emphasized in the design of doors, windows and the general layout. Buildings used by commercial firms, for instance, are mostly of the three-story variety. The first tall and spacious floor is used for business quarters, the second is a warehouse, and the third is a residential space.

Hongjiang's grandest buildings are undoubtedly its guildhalls. Taiping Palace (Baoqing Guildhall), for example, features a magnificent archway carved from a single piece of rock. In the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, merchants from all over the country sought to safeguard their common interests and promote friendship by building guildhalls in Hongjiang. This trend reached its zenith in the 1920s and 1930s, when nearly 130 guildhalls were built, receiving merchants from more than 20 provinces. According to one local elder, Guizhou Guildhall was the most luxurious. The hall still stands, its pillars made from single pieces of rock and the gate tower exquisitely decorated with carved dragons and painted phoenixes.

Hongjiang owed its former prosperity to its location on the Yuanshui River, a tributary of the Yangtze.

The City Today

Nowadays Hongjiang has more than 2,000 households. Most of the town's young adults have gone to other parts of the country to make money, leaving the elderly and very young at home.

Dong Hongmei, aged 59, is the daughter of a former dock owner, while her husband Yang Yun is the son of an erstwhile timber trader. They live in a yinzi building in the ancient city. The couple now operate a ferryboat belonging to a shipping company. They take turns at the prow pushing a long pole to help propel the vessel through the water, while their younger son Yang Mingye mans the boat's wheel. Dong Hongmei says most of her passengers are farmers who go to urban areas to sell vegetables. She charges them one yuan each for a round trip. A moored cement boat is used as a waiting room.

Their older son, with aid from his parents, invested RMB 120,000 in the construction of a big boat to transport timber from Hongjiang to Jiangsu and Zhejiang, and bring commodities back to Xiangtan on the return journey. Yang Yun says that since childhood life on the water has not been easy, but he believes one must learn to endure. While his elder son followed him into the shipping business at an early age, Yang Yun is determined to send his grandchildren to university at any cost, since the riverine shipping business is declining daily.

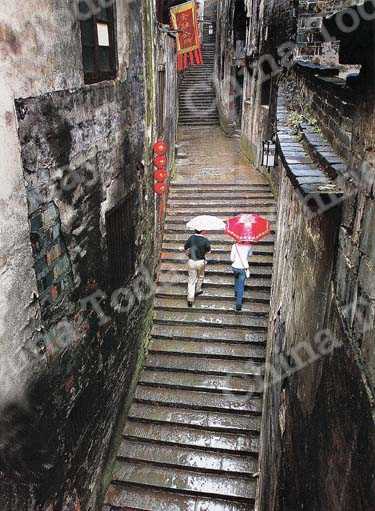

Hongjiang's ancient city lanes.

In another part of the town, Mr. Nie, the current host of the Gao Family Academy, runs a small inn. He never promotes the business, only receiving guests introduced by his friends. In old times, the descendants of the Gao clan attended classes here in a family-run school. Two rooms on either side of the first floor sitting room are used to accommodate guests; on the second floor are the host's living quarters. The guest rooms are four meters tall from floor to ceiling and the windows small. Along the walls are neatly arranged pieces of old furniture, and on the big bed hangs a mosquito net. The bedding is clean and tidy, the ornaments and decorations exude historical dignity. It is a soothing and nostalgic place.

Mr. Nie and his wife reside in this house, but their children are working in other parts of the country. A hospitable host, Mr. Nie often shows his guests around the town and introduces the local folklore. He also invites guests to dinner parties. He says he runs his small inn not to make money, but for the pleasure of playing the host. "If you come here during Spring Festival, every family will treat you as their guest," says Mr. Nie. Visitors can go door-to-door receiving treats and enjoying the special atmosphere of what was once one of China's busiest ports.

Tourist Tips

Getting there: Tourists can take a train to Huaihua City, Hunan Province, or fly to Huaihua's Zhijiang Airport, and then change to a bus at Huaihua South Bus Station. The journey to Hongjiang takes about two hours. The first bus departs at 6am, the last at 6pm, with services leaving every 30 minutes between those times.

Tourist Attractions Around Hongjiang:

1. Qiancheng is a well-preserved historical city with a history of 2,200 years, lying 20 kilometers north of Hongjiang. It is known as the "Grand View Garden" of western Hunan and "southern China's museum of ancient architecture." Its ancient layout of streets and lanes is well preserved. The city's Furong Tower is one of four famous towers in southern China.

2. The ancient Gaoyi Village of Huitong County is known as the "No. 1 Village in southern China" and a "living fossil of ancient residences." It is located 30 kilometers south of Hongjiang. In addition, dozens of ancient Dong and Miao ethnic minority villages dot the route from Hongjiang to Tongdao Dong Autonomous County along the National Defense Highway. These villages are built at the foot of mountains beside streams. Ancient Wind-and-Rain Bridges link the villages with the outside world.

Website: www.hongjiang.org

Copy Reference

Copy Reference