After a succession of meetings between labour and management in the second half of July 1951, the Tientsin Hengyuan Textile Mill, a prosperous enterprise financed by private capital, announced new production goals for the month of August. By the end of the month these goals had been exceeded. Profits were also 23 per cent higher than had been anticipated.

The experiences of the Hengyuan mill, which has existed for 31 years but never did well in the past, are typical of the whole private textile industry of China. So is the good business, and its confidence in its prospects at the present time.

When the Hengyuan Mill was founded a generation ago, its shareholders were mostly northern warlords who quickly turned its management into a sink of corruption and bureaucracy. Every factory official, big or small, made money for himself on the side. For instance, one man who was responsible for checking the weight of coal had a monthly salary of only 10 Yuan (about US $5.00 at the time), yet he bought himself twelve houses in Tientsin at the end of a few years. No wonder Pien Shih-ching, the white-haired bespectacled old director of the mill, says when he recalls the past: "Hengyuan used to be riddled with a thousand holes and covered with a hundred sores."

Director Pien Shih-ching of the Hengyuan Textile Mill confers with trade union delegates on production.

In 1928, when Hengyuan went bankrupt and closed down, no one was surprised. A year later, new bank loans were negotiated and an effort was made to reopen. Inefficiency and the competition of large amounts of Japanese yarn then being smuggled into Tientsin quickly caused its doors to shut again.

In 1936, Hengyuan was reorganized by a banking group which rid it of its feudal features and tried to run it along modern lines. Business was beginning to look up when Tientsin was occupied by the Japanese.

The Japanese were soon trying to get control of the Hengyuan mill, offering to "cooperate" with its owners. When this failed, they attempted to buy up all the shares. Failing again, they simply broke into the mill and robbed it of one-third of its machinery. Moreover, through a system of cotton rationing, they starved it of raw material. By 1942, only 800 of the 30,700 spindles were operating.

Victory over Japan did not help Hengyuan either. The new manager who took over under the Kuomintang gave key positions to incapable relatives and friends, whom the workers secretly called by such names as "The Thirteen Tyrants" and "The Four Bullies." These parasites cared nothing for the mill but took advantage of the Kuomintang inflation to make money on the black market while the enterprise itself rapidly heaped up debts.

A New Situation

In January 1949, Tientsin was liberated by the People's Army. A new economic policy was laid down to ensure that both labour and capital would benefit from a joint effort to increase production. But although the worst elements in its ranks no longer ruled the roost, Hengyuan's management did not at first understand the policy. Nor did the workers.

The leaders of the labour union were afraid that if they worked to increase production they would appear to be toadying to the capitalists and would therefore lose the confidence of the members who looked to them for better living conditions above all else.

Workers meet to consider how-best to carry out their pledges at the production conference.

On the other hand, the capitalists were filled with apprehension. They were not sure that they could make money under the new conditions. They were timid about making a real effort to promote production. They did not consult the labour union on their problems, because they thought it was out for higher wages only, and had no other concerns. To show that they were "progressive" they gave the union anything that it asked for, but they did it grudgingly.

In May, Liu Shao-chi, vice-chairman of the government and a senior leader of China's Communist Party, came to Tientsin and gave his famous talk on "benefits for both capital and labour." This greatly clarified the situation. The mill-workers came to understand that to produce more was the only way to improve their standard of living. Industrial output rose almost at once.

Labour-Capital Conferences

Regular conferences between labour and the mill-owners to discuss how to increase production, began in February, 1950.

At first, the management representatives were very dubious and uneasy about such conferences. On the one hand they had seen how workers in state-owned factories organized themselves to push production forward and thought the Hengyuan mill might derive similar benefits. On the other hand, they were afraid the discussions might get "out of hand." What if a worker got up at a public meeting and asked embarrassing questions about deadwood administrative personnel who might be holding jobs not because of any ability but as a result of ties of friendship or family with the owners?

To put it briefly, the management first thought only of how it might use the union rather than cooperate with it for the common good. It was this outlook which caused it to make the suggestion that, instead of joint meetings, two union delegates might be allowed to attend meetings of the administration.

The union turned down this offer, because it felt that it would reduce the role of its representatives from joint leadership in production to merely answering questions. To ease the fears of the owners, the union repeated once more that the only purpose of the production conferences would be to raise output, and that no decisions would be taken on which both sides did not agree. If either management or labour disagreed on a problem, no decision would be made. The owners fully accepted this formula and the conferences began on a regular basis.

Why Production Rose

Workers' delegates to the talks reported regularly to the rank-and-file, raising their sense of participation and consequently their enthusiasm. As a result, many knotty problems were solved. Here are some examples.

One of the spinning shops successfully increased its yarn output, but the winding shop, which was next in the production line, could not keep up with it. As a result, the unwound yarn piled up in great quantities. Management had tried to solve this problem by getting the winders to work overtime. This had only resulted in fatigue and illness among the workers without improving the situation.

When the question was submitted to the conference, the union undertook to seek the workers' advice on how to remove the bottleneck by improving work-methods and granting bonuses, instead of overtime or speed-up. The management was skeptical saying, "Let's see if you can convince them?" The results fully justified the union suggestion, and the lag was successfully eliminated.

In the weaving department, the owners had tried long and unsuccessfully to get each worker to mind eight looms instead of four or six. The union pointed out that the trouble lay not in technique but in the wage system. When the workers themselves were enlisted in working out an equitable wage scale, the previously "insoluble" question turned out to be quite simple.

Hengyuan Becomes a Model

Another spectacular improvement took place in the elimination of waste. The union mobilized the workers to devise ways of cutting it down. As a result, the average daily waste was reduced from 500 lbs. to 270 lbs. It was then that director Pien declared: "I've been running factories for scores of years, but I could never imagine anything like this before."

Last spring, after a year of experience, the Conference of Labour and Capital had acquired enough confidence to launch a three-month work competition. This led to the breaking of all previous production records at the Hengyuan mill. The mill was subsequently elected a model industrial enterprise of Tientsin.

In July 1951, a further step was taken. The Hengyuan mill, for the first time in its history, drew up a comprehensive production plan. This plan was thoroughly discussed at production conferences in each shop. It not only set output targets but also a system for checking up on quality.

Work competitions are now a regular feature of Hengyuan's life. Every one of those already completed has corrected some technical or organizational fault hitherto characteristic of private factories in China. More scientific procedures have resulted from each.

Better Work: Better Life

Wage standards have been readjusted. All workers, technicians and management personnel are now paid according to actual function and ability on the job - not according to custom or connections.

Personnel-shifts have been made in accordance with the needs of productive efficiency.

The mill owners have come to modify their idea that low wages are the only source of prosperity. They have learned from facts the importance of satisfying the workers' demands for a betteer life. Appropriations from profits have been used to improve the mill hospital and to build spare-time schools for the workers and creches for their children. The workers now eat meat and polished rice instead of rough grains as before.

The business of the Hengyuan cotton mill is better than it has ever been. Profits by the end of 1949 were already sufficient to pay off all its accumulated debts, with plenty to spare. Since then a substantial surplus has been built up.

No longer menaced by the causes which made life for Chinese factories so precarious in the old days of bureaucratic extortion and unfair imperialist competition, the owners of the Hengyuan cotton mill are now buying new machinery and planning to set up a mill in west China. They have also sent out salesmen all over the country to collect orders for Hengyuan's constantly growing output.

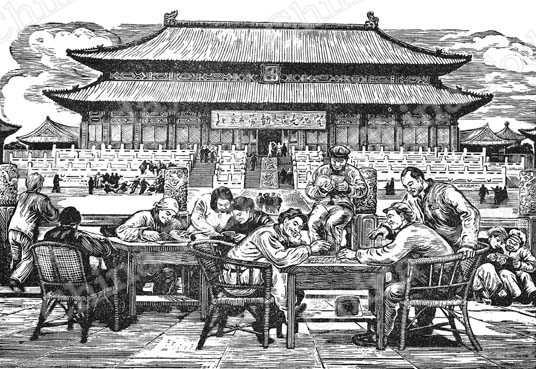

THE WORKERS' CULTURAL PALACE Woodcut By Ku Yuan

Copy Reference

Copy Reference