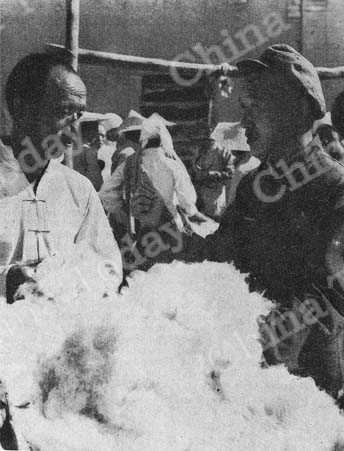

A peasant takes his cotton to market. China's 1951 cotton crop is the biggest in her history.

Villages in China's cotton-growing areas were festive during the sale season in 1951. The buyer was the People's Government. Prices were good. Carts and pack-mules loaded with huge bags of cotton were colourfully decorated with red and green flags reading, "Join the Sell-Cotton-to-the-Government Patriotic Contest." Peasants accompanied the carts and mule trains beating on drums and cymbals and dancing the popular yangko (harvest dance).

In each district, peasants competed to be the first to sell stocks to the government. Many growers also wrote letters to textile workers in Shanghai, Tientsin and Tsingtao, pledging to keep the mills supplied. Village challenged village to bring more cotton to market. Buyers sent by the National Cotton & Yarn Corporation stayed up late into the night working on their accounts.

Problem Last Year

At one period during the spring of 1951, textile mills in Chinese cities found themselves in difficulties. Land reform and government assistance to cotton-growers had made 1950 a good year for the peasants. They had plenty of cash in their pockets after selling only a portion of the cotton crop in the fall, and were therefore not particularly interested in further sales in the spring. The peasants stored their cotton as city people save money. Some hoarded against a coming wedding. Others wanted to keep the cotton "for the women to spin." One peasant simply said: "It does my heart good to see it there, all white and puffy, when I come in from the fields. Besides, I don't need cash right away."

The Government Calls

On June 1, 1951 the People's Government published a directive, frankly describing the seriousness of the situation. It called upon the peasants to sell their cotton stocks at once. The price offered was a fair one. Peasants who did not wish to sell immediately were urged to deposit their cotton in government warehouses, to be paid for at the current price any time they wished. "This will be considered a patriotic action, an important contribution from the peasants to the nation," the directive said.

In villages in every cotton-growing area, along the Yangtze and Yellow rivers, in the northeastern provinces and the vast plains of the Northwest, peasants gathered to discuss the directive. None of them had realized up to then that it made much difference whether they sold their cotton or held it until they needed more money.

Discussion in the Villages

The assembled peasants recalled the past. They related how, before liberation, they used to sell all their cotton and still not have enough to pay rent and taxes. The crop had hardly been picked when the Kuomintang paochia chang (constable) would appear with demands for money. Most families could not keep enough cotton to make padded winter garments, and had to shiver through the cold weather in thin rags. The spring often found them with no rice. Many was the year when whole villages lived on weeds and tree bark till the next harvest.

By contrast, the peasants could now point to all the new property that they had been able to buy after the People's Government relieved them of the load of supporting landlords and corrupt officials in luxury. The general sentiment was well expressed by peasant Shen Ping, who declared at one village meeting: "We mustn't forget past pain just because our wounds have healed. To protect our present good life, let's help the government which has helped us."

Husbands and Wives

As a result of similar meetings conducted by the Democratic Women's Federations, the peasant women soon came to vie with their husbands in offering cotton for sale to the government.

Peasant seller talks grade and price with a buyer for the cooperatives.

Peasant Wang Tien-tai of Hoting had made a pledge to sell 1,100 lbs. to the cooperative in his village. He found a little trouble in explaining just why he had done it to his wife at home. To his surprise, when the women held their own meeting, his wife got up to speak, mentioned the amount of cotton in the house, and offered it herself "to make our good life last."

Another woman, Wang Ching-chih, stood up and said: "If the men can be patriotic, I don't see why we can't. I went through enough hell when the Japanese devils were here. I'm not going to go through the same thing with the Americans. I have some ginned cotton stored up, and I'm going to sell it to the government."

In a cotton village, in Chengan district, each family met separately to decide what to do. Peasant Liu Ching-kwei, for example, asked the women in his house: "Do you want to wear flower-print dresses?" When the women said they did, Liu clinched the argument: "Then we must sell our cotton to the government, which will send it to the mills to have fine cloth woven and printed for you." There were no further objections and Liu delivered 1,100 pounds.

Why Peasants Responded

Why did such simple discussions suffice to bring cotton to the sale stations? Because the People's Government had already won the loyalty and confidence of the growers, not by words but by real proofs of concern for their interests.

The government had been responsible for keeping the ratio of cotton to grain prices at a constantly fair rate, enabling producers to eat well at all times. It had protected them from loss due to their own actions. In the summer of 1950, when many had dumped stocks fearing that the Korean war would spread to Chinese cities and mills would no longer buy, the government had kept speculators from pushing prices down.

The government had also helped cotton growers to improve their work with technical advice, providing them with equipment and services. When cotton was being planted last April, it sent specialists to the countryside to help the cotton growers conquer drought. It extended loans to sink thousands of new wells, and dig irrigation ditches. It mobilized six million peasants in Hopei province to spray 1,480 tons of insecticide, which saved 2,000,000 acres of the cotton crop.

The government had sold soybean cake, a high-grade fertilizer, to growers at low prices and on easy credit terms. Finally it had helped cotton-growing villages in every problem of livelihood, seeing that they were supplied at all times with food, cloth, salt and other daily needs. It had also sold them cheap fuel for cooking and winter heating, a constant problem to Chinese cotton farmers who have no stubble and straw to burn like grain-growers.

Since liberation, large amounts of coal have been brought to the villages. In the past, only city people in China had coal to burn.

More Abundant Life

As a result of this varied aid, production increased and the livelihood of the farmers improved beyond recognition. In 1950, even though the growers did not sell their whole crop, their purchasing power outstripped the goods within reach.

An investigation in Hantan, Hopei province, showed that peasants were eating fine flour and polished rice instead of the coarse foods of the past. During January 1951, no less than 1,170,000 feet of cloth were sold in the district; a third more than in January 1950 when there was an inflationary buying spree. Peasant women had new flowered dresses and bedspreads. Children's clothes were fresh and gay.

Weddings increased, with consequent good business for the silk merchants in Kiangsu and Chekiang provinces. New houses had tile floors instead of oiled paper in the windows. Flashlights and bicycles were in big demand. In Weihsi village, after the 1950 harvest, every one of the 400 families bought a new electric torch and one out of every four families acquired a bicycle.

Textile mills, which used to import cotton, now get ample domestic supplies.

Their cotton sold, peasants at this cooperative market collect their money.

The peasants themselves can't stop talking about their new prosperity. They tell each other: "There used not to be a bicycle in the whole village; and now look!" Stockings, rubbers, sweaters, knitted underwear, thermos bottles are becoming necessities to people who used none of these things in their whole previous lives. Many village girls now buy high-grade face towels, hair lotions and cold cream of Shanghai manufacture. A pedlar has only to push his cart into a cotton-growing village to find his needles, combs, hairpins and other goods disappear and himself the possessor of a thousand or so pounds of cotton.

The technical equipment of cotton farms is also growing rapidly. Hundreds of new carts, as well as used auto tires, to replace the previous iron wheel-rims, have been sold in Hantan district since the harvest. In Hunghsiang alone, hardware merchants sold 63 1/2 tons of metal farm implements in one month. Not long ago, cotton growers of Hsiaoho village sent delegates to Peking to have a look at some tractors.

More and More Cotton

The area under cotton in 1951 was 30.2 per cent greater than in 1950. It was more than 17 per cent greater than the highest acreage recorded in pre-war years.

Owing to the working enthusiasm and improved technique of the peasants, the average yield per acre was also higher, by 33 per cent, than the best pre-war figure.

Copy Reference

Copy Reference