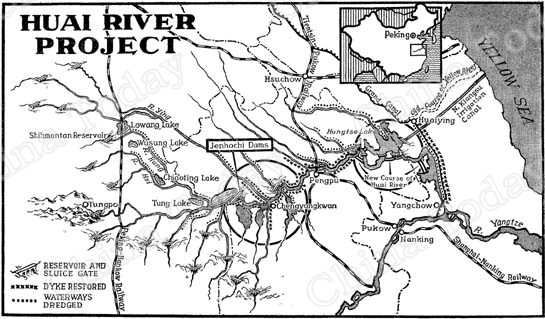

The greatest water control effort in Chinese history is now underway in the valley of the Huai river, which contains over 50 million peasants and covers one seventh of all China's cultivated land.

The work was begun in November 1950. Eight and a half months later, in July 1951, its first phase had been successfully completed. This result was achieved thanks to the planning and leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and the Central People's Government. It was brought about by the organized energy of 2,200,000 peasants who did the excavation work, of thousands of Chinese workers and technicians whose labour and ingenuity supplied machinery and installations which previously always had to be imported, and of hundreds of conservancy engineers applying advanced but at the same time economical methods developed in the Soviet Union.

The primary aim of the project is to put an end to the constant flood menace in the Huai valley. Already, as a result of the first phase, the population is safer from floods than ever before. When the whole scheme is completed, within three to five years, floods will be banished altogether. Hundreds of miles of waterways will become navigable. Millions of acres of farmland will be secured against drought by irrigation. The waters of the Huai and its tributaries will begin to generate large amounts of electric power for the people.

The accomplishments to date include the creation of 1,120 miles of earth dykes, the dredging of 480 miles of river beds and the building of 56 concrete locks and other installations. Approximately 158 million cubic feet of earth have already been moved. Work has begun on 16 major reservoirs, several large dams and a great network of irrigation ditches, culverts and other drainage facilities throughout the area.

What has been done in these months testifies to the tremendous energies awakened by our revolution. Already it exceeds, in volume and effectiveness, all the work done in the Huai valley in hundreds of years of past history.

The Huai and Its History

The Huai is one of the big rivers of China. Rising in the Tung Po mountains, it runs for 683 miles through the three important provinces of Honan, Anhwei and Kiangsu. In the north the Huai valley connects with that of the uncontrolled Yellow River. In the south it connects with the Yangtze valley. In the east, the Huai river flows into the Yellow Sea.

Passing through Honan and northern Anhwei, the river is fed by ten large tributaries and many smaller ones. Some of them, flowing down steep mountains, are extremely rapid and turbulent. The Huai itself by contrast is wide and deep, calm and navigable for most of the year. But in the rainy months of July and August the inflow from the tributaries frequently causes it to flood great areas. This tendency is aggravated by four "bottlenecks" along the river's course. When in flood, the "young maiden," as the Huai has been called in tribute to its usually serene disposition, has often turned into a bearer of death and destruction.

Another cause of floods on the Huai river, and much more serious ones than the almost annual inundations of the tributaries has been its northern neighbour, the great Yellow River. There are no mountain ridges to divide the Yellow River from the Huai. The plateau that separates them is 100 to 150 feet higher in the north than in the south. When the Yellow River overflows, its waters often come down the slope to try and usurp the bed of the Huai, filling it up with silt. This has often caused the Huai, in its turn, to burst south into the Yangtze.

For 661 years of Chinese history, between 1194 A.D. and 1855 A.D., the Yellow River emptied into the sea through the Huai and had no other outlet. During these centuries, it filled the Huai with sediment, raised the water-level in many of the lakes connected with it, and generally slowed its course. It also wrecked the whole lake system between the Huai and the Yangtze and created a constant threat of flood to 10 million mow (about 1.7 million acres) of rice fields along the Grand Canal.

In 1855, when the Yellow River abandoned its southern course and began to flow into the sea north of the Shantung peninsula along its present bed, the Huai river also changed its habits completely. Its old mouth became completely blocked with silt. Instead of reaching the sea, the Huai began to flow into the Yangtze.

The situation remained more or less constant until the reactionary Kuomintang government, caring nothing for the people, broke the Yellow River dykes at Huayuankow in Honan for what it considered to be a temporary military advantage. As a result, tremendous areas were flooded. The Yellow River once more invaded the Huai, and flowed to the sea through the Huai for nine years, until 1947. The whole drainage system of the Huai valley was destroyed. The mouths of many of its tributaries were stopped with mud. Much of the network of irrigation ditches in the Huai valley was completely obliterated. The bed of the Huai itself filled up considerably. The flow of the Huai river at Pengpu fell from 307,000 cubic feet per second in 1931 to 297,000 cubic feet per second in 1950. Nevertheless the water level rose by about three feet in the same period. The reduced capacity of the Huai resulted in a further increase in flood threats.

A Thousand Floods - And Nothing Done

What the Chinese people have suffered from failure to control the Huai river may be gathered from one figure. Our historical records count no less than 979 floods along its course between 246 B.C. and 1948 A.D. In other words, the Huai has produced a flood every two years for some seventy generations!

There are three basic conditions making for floods along the Huai. They have always been the same and have been known for centuries. In the headwaters and along the tributaries of the Huai, there have not been enough installations to check and hold water. Its middle reaches have lacked storage reservoirs. In its lower valley, close to the sea and the Grand Canal, the outlets were too limited to hold the flow. It has been known for a long time that no single one of these conditions could be remedied independently. The river could be controlled only if all three types of work were undertaken at once.

Map by Mei Wen-huan.

Such an overall job of reclamation was precisely what old China, with its predatory special interests, clashes between regional groups of exploiters and ultimate semi-colonial subservience to imperialism had neither the motive nor the capacity to undertake. On the contrary, the feudal and dynastic conflicts of the old society, its long decay and the disintegration that attended its death-throes frequently destroyed even the local attempts at control in which the people themselves invested so much labour.

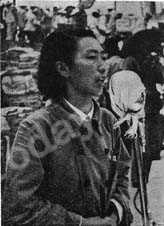

Ch'ien Chen-ying directed the construction of the giant Jenhochi dams. She is assistant chief engineer for the entire Huai river project.

After the Yellow River rushed into the Huai in 1194, neither the rulers of the Sung dynasty nor those of the Yuan (Mongol) dynasty which succeeded it undertook any measures at all.

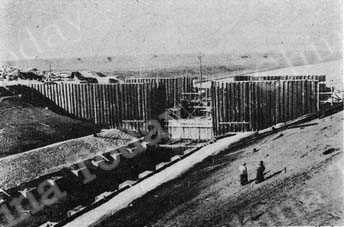

The Huaiyin lock, on the lower reaches of the Huai, is one of 56 locks already completed in the first phase of the Huai river project in 1951.

The two subsequent dynasties, the Ming (1368 - 1644) and the Manchu Ching (1644 - 1911 A.D.) did allocate great sums of money for work on the Yellow and Huai rivers. These sums, wrung in taxes from the people, were quite sufficient to return the Yellow River to its old course and dredge and adjust the entire Huai. What happened, however, was that a part was misappropriated by officials and the rest was used in a greedy and short-sighted way.

With the capital established in Peking, the Ming and Ching emperors thought only of the Grand Canal which carried about 200,000 tons of tax rice to Peking annually for the needs of the court. Instead of getting at the root of the Huai floods, they piled up ever-higher dykes and embankments to keep them away from the canal. This kind of dyke building merely aggravated the floods in higher areas by damming them up. When the pressure of water proved too great and the canal dykes were breached, which happened frequently, the lower valley of the Huai, in north Kiangsu, also suffered disastrous inundations.

In 1855, when the Yellow River turned once more to its northern sea exit, the Manchu empire could think of nothing but to "let nature take its course." The warlord rulers of the early years of the Republic did no better. After the calamitous floods of 1931, the Kuomintang regime, which had by then been in power for four years, began to speak loudly about conservancy work on the Huai. But the reactionary Chen Kuo-fu, then Chairman of the Kiangsu Provincial Government, insisted that work be done in his province alone. The interests of the inhabitants of the upper valley, and the correct method of controlling the Huai, were again ignored for the interests of local landlords. Money was squeezed from the people as usual, some construction work was begun, but the whole "plan" and its execution soon dissolved in the rackets and corruption typical of "politics" at the time.

By breaking the Yellow River dykes in 1938, and thus deliberately destroying the Huai river system no less effectively than the natural floods of 1194 and 1855 A.D., the Kuomintang reactionaries exposed their own complete bankruptcy and left the people a heritage of woe.

The Project's Origin and Goals

As a result of past abuses, another serious flood took place in the Huai valley in 1950, the year of its liberation. More than 40 million mow (6.6 million acres) of cultivated land were submerged. The distress that attended this flood, however, was much less than in comparable occurrences in the past. The People's Government undertook immediate remedial measures which saved lives and property. Flood-stricken people were rapidly organized for labour and hundreds of thousands of tons of rice were brought to feed them. Clothing was collected throughout the country and those who had lost their own effects were re-equipped. The people who had never experienced such care and aid from the government and the whole country before, worked with will and hope to mend dykes and otherwise limit the spread of the flood. There was no starvation.

The 1950 flood occurred in July. In August, the Administration Council of the Central People's Government, acting on a directive from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, met to consider how to harness the Huai. In September, it adopted a resolution to initiate the giant project now under way. Water conservancy experts from all parts of the country, summoned to Peking, drew up necessary plans in the short space of two months. By November, work was in progress on the actual sites.

Out of consideration for the people, the time-table for the first phase was so arranged as to rid the Huai valley of the threat of serious floods from 1950 on. Successful meeting of the July deadline has made this goal a reality. When the rainy season arrived last year, the Huai was protected not only by relatively advanced works of a permanent nature but also by temporary structures to take care of current emergencies. There was no flooding in 1951.

Longer-range river control plans, for the first time in history, were based not on regional claims but on the needs of the Huai valley as a whole, the upper reaches as well as the lower, the battle against droughts as well as the battle against floods. The irrigation systems that will arise will water from six to nine million mow (one to 1.7 million acres) of land in the upper reaches of the river and 35 million mow (6 million acres) each in the middle and lower valley. In navigation, the controlled river will carry transport where it is most needed, between points that play an important part in the interchange of commodities between city and country, producers and markets. Steamers plying the Grand Canal will be able to turn westward and proceed along the Huai to points in Honan beyond the Peking-Hankow railway. The Tientsin-Pukow and Peking-Hankow railways will be connected by a new water link.

As for electric power, there are no natural sites for its production in the broad, flat Huai valley. But the new reservoir, dyke and sluice systems will provide opportunities to generate a sizable supply for the needs of both agriculture and industry in the region.

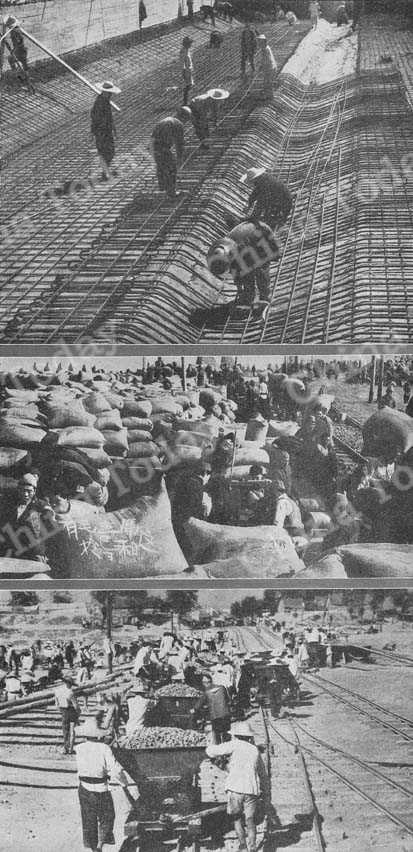

Workers swinging 220-lb. stones to compact earthwork in the traditional Chinese way. Later there will be machines to do this.

Work Done and to be Done

I would now like to outline in some detail how the Government Administration Council analyzed conditions on the Huai river and the remedial measures already taken and to be taken.

Generally speaking, it was found that the existing drainage system of the Huai was capable of holding only half its water load in cases of flood on the scale of 1931 or 1950. Since the rainfall in the Huai valley in July, August and September is out of all proportion greater than that in other parts of the year, the risk of comparable floods would be constant so long as this situation was not changed.

At the same time, due to the uneven distribution of rainfall, the valley generally suffered from droughts in the spring, when the peasants were most in need of water for their fields. The problem with regard to the Huai was therefore not merely to speed up the flow to the sea, but to store the water where it would be required for irrigation purposes in the dry season.

To prevent the river from becoming unduly swollen by rains, it was decided to dredge the entire drainage system of the Huai of the Yellow River silt that blocks it. To store water where it is needed, dams and reservoirs were planned at suitable places.

In the mountainous upper reaches of the Huai, trees are being planted and small basins, tanks and dams constructed to slow the flow of water and prevent soil from being washed off the hills by torrential downpours. The sixteen big artificial reservoirs comprising the system, with a total capacity of 109 billion cubic feet, are to be installed along the upper tributaries - the Hung, Hsi, Kuan, Pu and Ying rivers. One, the Shihmantan reservoir at the headwaters of the Hung, has already been completed. Two others will be in operation by the end of 1951. Drainage of excess water from the slopes is to be accomplished by local ditches dug by the organized effort of the people.

Fu Tso-yi conversing: with the local peasants while inspecting the work of the Huai river project.

The new reservoirs are being supplemented by work on the Lowang, Chiaoting, Tung and Wu-sung lakes in Honan province. These "lakes" were formerly no more than low-lying marshes connected with the course of the river, too frequently flooded to serve as cropland yet not storing enough water at the right times. The job of converting them for storage purposes is to be finished in 1951. With their help, the total storage capacity in the upper reaches of the Huai will be brought to 60 billion cubic feet, helping greatly to secure the region against flood while the new reservoir system is still incomplete. Moreover, since water will be allowed to flow into them only when flood conditions require it, the lake beds will be cultivated to produce at least one crop a year. This will greatly benefit the entire area and its people.

Lower down, in north Anhwei province, there are other marshy lakes on either side of the Huai. Excluding the big Hungtse lake, they have an area of 741,320 acres. Their capacity will be brought to 254 billion cubic feet by the end of 1951. In this way the flow of the Huai in its middle reaches will be brought under effective control.

The main control installation in the middle reaches, located at Jenhochi in northern Anhwei province, has already been built. It consists of three parts. The first is a fixed deep channel 255 feet wide. The second is a long movable dam 984 feet wide, with nine sluice gates - five of 147 feet each, one of 69 feet and three of 48 feet - across the broadened river bed. The third is a 585-foot movable dam at the entrance with two sluice gates of 147 feet each and four of 69 feet.

Work at Jenhochi was begun in April and finished in July 1951. To achieve it over 200,000 tons of industrial material, mainly cement and steel, were brought to the site. The 1,300 tons of steel sluice gates and machinery, of a type China always imported in the past, were successfully made in Shanghai in the space of two months and installed by technicians and workers from that city who came to Jenhochi. Concrete mixers on the dam sites were also of Chinese manufacture. The fulfilment of this project was an impressive demonstration of the organizational and industrial capacities already present in our country but never previously used.

The Shihmantan reservoir, the Jenhochi installations and the dyke construction elsewhere have already considerably mitigated the danger of flood in the part of the Huai valley that lies in Honan province, secured northern Anhwei against dyke breaches and guaranteed the wheat crops in that area against flood damage.

The work in the lower reaches, directed mainly at strengthening dykes along the Grand Canal and renovating local waterways leading into the Huai, will do the same thing for north Kiangsu.

The removal of the perennial causes of floods along the Huai is thus already considerably advanced. With the completion of the entire project, the scourge of thousands of years will cease to exist.

This view of the tranquil Huai explains why it is known as the "Maiden River" - when it is not in flood.

How Our People Are Working

I myself travelled along the entire course of the Huai river earlier last year, inspecting the progress of the work over a distance of more than six hundred miles.

What impressed me most of all on this trip was the change in the outlook of our peasants following the land reform, which for the first time has given them land of their own, free of both rents and debt. This change is decisive for the harnessing of the Huai, because the peasants engaged on the project know they are toiling for themselves. They work with an enthusiasm inconceivable in the water conservancy undertakings of the past, when they were employed or driven by landlord interests which reaped the full benefit of any improvements achieved. It is their own land, their own crops that they are now protecting - and they know it.

Needless to say this proud consciousness has also improved the relations between the workers and the leading and technical personnel. With all ranks now working for the same goal instead of one exploiting the other, mutual confidence and appreciation have replaced the former hostility and compulsion. One has only to see these millions of people working in a harmonious and organized manner, in the full knowledge of what they are doing and why, to realize that our country has at last really risen to its feet. With the titanic force this has generated one feels there is nothing we cannot accomplish!

Another strong impression is the closeness of the people to the Communist party and the government - their party and their government. In giving the people land and power over their own destinies, the party and government sank deep roots in every village and hamlet. In the 1950 flood, tens of thousands of party and government personnel moved into the afflicted areas, sharing the dangers and privations of the peasants, leading them in the fight for food, helping them in the autumn planting of devastated fields, organizing mutual aid groups and subsidiary occupations such as mat-weaving, hemp processing and fishing - in a word, saving their lives. This experience, unheard of in the old China, has created a unity and intimacy as strong and close as that of flesh and bone. Now the government has only to call and millions of peasants respond.

(Top) Steelwork on a reinforced concrete dam. (Middle) To feed the workers, thousands of tons of rice were brought to Huai river building sites. (Bottom) Rails were laid for the transport of broken stone and other materials.

The beat of drums and clash of cymbals can be heard all along the Huai during rest periods and at night, as groups of workers relax with dancing and music.

In responding to the mobilization to free their valley of floods altogether, the people of the Huai river have seen trains, steamships, motor-driven junks, wooden boats and long lines of trucks come unendingly from all parts of the country bringing needed materials, administrators, technical men, doctors, nurses, teachers, and lecturers, actors and mobile moving picture teams. They have convinced themselves once more that they have only to work for their own interest to receive all the aid and comfort that all of China can give. They understand that they are no longer isolated, no longer ignored or oppressed but great, strong and self-reliant.

The viewpoint of the peasants themselves is no longer local. They know that it was Chairman Mao Tse-tung who decided to tame the Huai river and avert new calamities without delay, without being deterred by the other grave and urgent problems that face the country. They know that the People's Government has cut through all the old regional selfishness to lay strong hands on the Huai and turn it from a tyrant into a servant of the people. They know that water conservancy, and the Huai river work in particular, has been assigned a high percentage of the national budget.

The unprecedented Huai river project both benefits our agriculture and helps prepare for great new steps in our industrialization. It is changing the face of a large section of the country. While howls for war are heard throughout the imperialist world, China is engaged in a gigantic peaceful effort that once more demonstrates not only the constructive ability of our people but their will and their strength for peace.

[注释]

NOTE: A number of figures wrongly given in the article as it appeared in the first printing of this issue of the magazine have now been corrected.

Copy Reference

Copy Reference